From First Principles:

Toward a Truly Limited Government

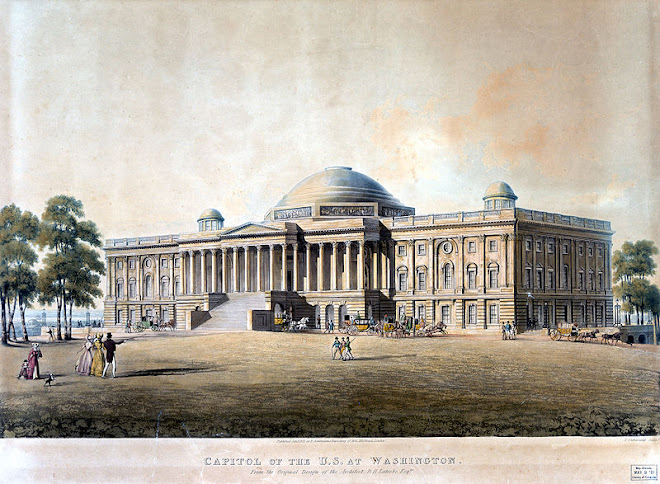

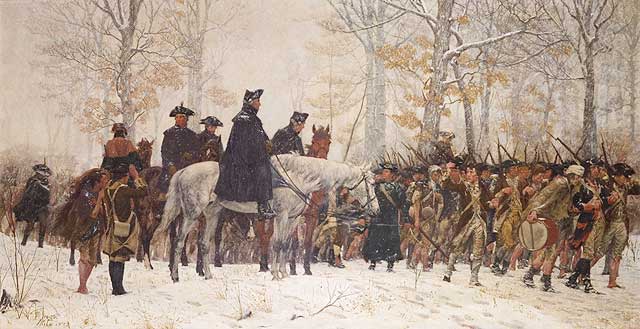

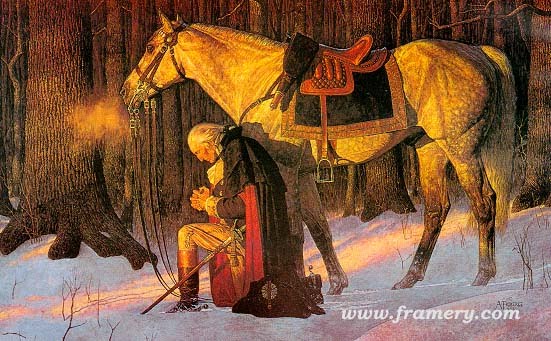

The great challenge of democracy, as the American Founders understood it, was to restrict and structure government to secure the rights articulated in the Declaration of Independence—preventing tyranny while preserving liberty. The solution was to create a strong, energetic government of limited authority. Its powers were enumerated in a written constitution, separated into departments and functions, and further divided between national and state governments in a system of federalism. The result was a framework of decentralized constitutionalism and a vast sphere of freedom, leaving ample room for republican self-government.

The Founders understood that size indeed matters, but even more important is the purpose and operational structure of government. Small government does not mean the same thing as limited government. The Founders understood this well; it is a constant theme in their writings, emphasized especially in The Federalist. They went to great lengths to moderate democracy and limit government not merely by parchment barriers but also through structural mechanisms and “auxiliary precautions” such as the separation of powers and checks and balances.

And yet here we are today, covered by a vast web of rules and regulations, endless policies and programs, all emanating from a massive central government that dominates virtually every area of American life. Its authority is all but unquestioned, seemingly restricted only by expediency and the occasional budget constraint.

What happened?

We can trace the concept of the modern state back to the theories of Thomas Hobbes, who wanted an all-powerful “Leviathan” that would impose a new order, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who favored an absolute state to achieve absolute equality. Alexis de Tocqueville warned us of a new form of despotism in such a centralized, egalitarian state: it might not tyrannize, but it would enervate and extinguish liberty by reducing self-governing people to “nothing more than a herd of timid and industrious animals of which the government is the shepherd.”

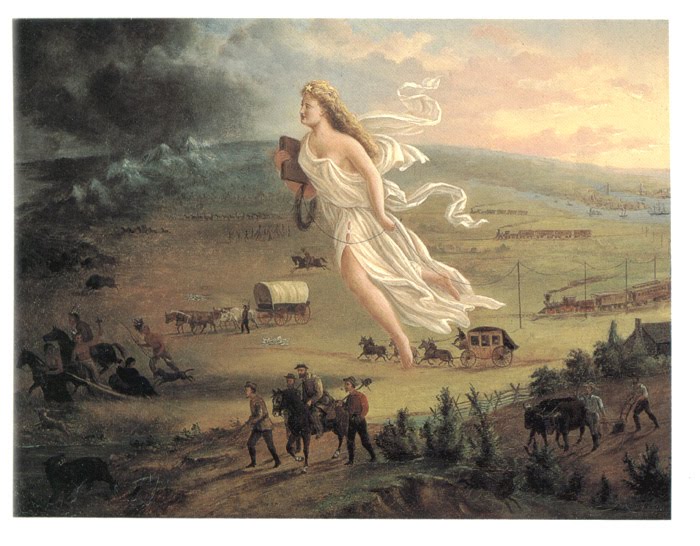

The Americanized version of the modern state was born in the early twentieth century. American “progressives,” under the influence of German thinkers, decided that advances in science and history had opened the possibility of a new, more efficient form of democratic government, which they called the “administrative state.” For this to be possible, however, government could not be restricted to securing a few natural rights or exercising certain limited powers. Instead, government must become dynamic, constantly changing and growing to pursue the ceaseless objective of progress.

Over the course of the twentieth century, our national government (followed quickly by state governments) became bloated, overextended, and unrestrained, oblivious of its core functions, operating far beyond its means and outside its proper constitutional bounds. In assuming more and more tasks in more and more areas outside of its responsibilities, modern government has caused great damage. By feeding an entitlement mentality and dependency rather than promoting self-reliance and independence, administrative government encourages a character incompatible with republicanism. The extended reach of the state—fueled by its imperative to impose moral neutrality on the public square—continues to push traditional social institutions into the shadows of public life, undermining respect for institutions meant to strengthen the fabric of America’s culture and civil society.

The size of government must be vastly reduced. But the modern form of government—in which everything is socialized under the unlimited scope of the administrative state—is the real problem.

True self-government cannot be revived without a decided reversal of administrative centralization in the United States. This requires that we seriously revisit the classic argument of federalism, but not by merely shifting bureaucratic authority to states that are themselves bureaucratic and increasingly dependent on federal largesse. What we need is a significant decentralization of power, and of vast areas of policymaking, moving from the federal government to states, local communities, neighborhoods, families, and individual citizens. Public welfare, education, and health care—all issues that in recent decades have become concerns of the federal government, but are better dealt with at the state and local levels of government (not to mention by families, community organizations, religious congregations, or private markets)—are ripe for this kind of reform. We cannot claim to govern ourselves if every question, problem, and aspect of our lives demands a new government program.

At the same time, our experiment in self-government cannot survive if we become a nation of disconnected, autonomous individuals. The American system of decentralized governance, which allows political bodies closest to the people to decide a multitude of issues within their own purview, is an important feature of our constitutional structure. It is through our relationships with neighbors, friends, and fellow countrymen—in local communities, churches, schools, and private organizations, in workplaces and through economic exchange—that we acquire the habits, practices, and spirit of Americans, strengthening our virtues, work ethic, and mutual responsibilities.

Over the next months and years, and the next few elections, important questions about the form of modern government will be decided, perhaps definitively, one way or the other. Either the party of the modern state will unify its control and solidify its centralized model of government, or a new coalition of its opponents—unified by a healthy contempt for bureaucratic rule and a determination to reassert popular consent—will gain control of the political institutions of government and begin the difficult task of restoring real limits on government. In this choice, all rests on the continuing capacity and resolve of the American people to govern themselves.

Matthew Spalding is Vice President of American Studies and Director of the B. Kenneth Simon Center for American Studies at the Heritage Foundation and author of We Still Hold These Truths, available from ISI Books.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment